Leaf's Reviews

Children's, Middle Grade, and Young Adult Book Reviews

Dangerous Games is another “filler” book about Dido’s adventures between the events of Nightbirds on Nantucket and (presumably, since I’ve never read it) The Cuckoo Tree. I have chosen to read these books chronologically, though I wonder if it might have been better to read them in publication order, as Aiken once again incorporates a much more magical world than was in any of the first three books. This makes me wonder if fantasy elements are more prevalent in the later books, or if Aiken decided to play off the “magical exotic island” trope.

Dangerous Games is another “filler” book about Dido’s adventures between the events of Nightbirds on Nantucket and (presumably, since I’ve never read it) The Cuckoo Tree. I have chosen to read these books chronologically, though I wonder if it might have been better to read them in publication order, as Aiken once again incorporates a much more magical world than was in any of the first three books. This makes me wonder if fantasy elements are more prevalent in the later books, or if Aiken decided to play off the “magical exotic island” trope. Given a Newbery Honor in 1983, Homesick: My Own Story is the memoir of Jean Fritz, best known for her children’s history books, and her life growing up in China during its Republic years (Sun Yat-Sen, Chiang Kai-Shek, and civil war). It describes some of the turmoil in China at the time, particularly the siege of Wuchang near Hankow (where Jean lived with her parents), as well as some of the cultural opposition to the British and American presence in China. However, since this is a memoir, most of it is filtered through Jean’s eyes, so most of that is only focused on towards the end of the novel when Jean and her parents are preparing to leave China.

Given a Newbery Honor in 1983, Homesick: My Own Story is the memoir of Jean Fritz, best known for her children’s history books, and her life growing up in China during its Republic years (Sun Yat-Sen, Chiang Kai-Shek, and civil war). It describes some of the turmoil in China at the time, particularly the siege of Wuchang near Hankow (where Jean lived with her parents), as well as some of the cultural opposition to the British and American presence in China. However, since this is a memoir, most of it is filtered through Jean’s eyes, so most of that is only focused on towards the end of the novel when Jean and her parents are preparing to leave China. Jahanara: Princess of Princesses is at first glance the story of a relatively unknown princess of the Moghul Dynasty. And, due to the rigid and limited roles and customs for women and the fact that Jahanara mentions how a princess of her position doesn’t marry, you might wonder why have a book about this princess at all. But, of course, despite Jahanara’s relative lack of power (she does go on to become an advisor to the emperor) and overall lack of presence in history (only really known as the emperor’s favorite daughter), this book does communicate a great deal about the Moghul dynasty, specifically about Shah Jahan and the Hindu/Muslim clashes. And if you don’t know who Shah Jahan is, just think of the Taj Mahal—he’s the one who constructed it for his wife (the mother of Jahanara).

Jahanara: Princess of Princesses is at first glance the story of a relatively unknown princess of the Moghul Dynasty. And, due to the rigid and limited roles and customs for women and the fact that Jahanara mentions how a princess of her position doesn’t marry, you might wonder why have a book about this princess at all. But, of course, despite Jahanara’s relative lack of power (she does go on to become an advisor to the emperor) and overall lack of presence in history (only really known as the emperor’s favorite daughter), this book does communicate a great deal about the Moghul dynasty, specifically about Shah Jahan and the Hindu/Muslim clashes. And if you don’t know who Shah Jahan is, just think of the Taj Mahal—he’s the one who constructed it for his wife (the mother of Jahanara). When You Trap a Tiger reminded me a great deal of a Newbery Medal book from a couple of years ago, Merci Suarez Changes Gears. It features a fairly similar plot (sickness in an elderly family member) and a focus on a specific culture (Korea in this one). It’s also similar in writing, delivery, and pace, and I liked it about as much.

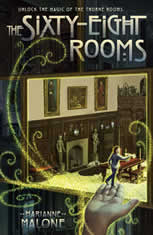

When You Trap a Tiger reminded me a great deal of a Newbery Medal book from a couple of years ago, Merci Suarez Changes Gears. It features a fairly similar plot (sickness in an elderly family member) and a focus on a specific culture (Korea in this one). It’s also similar in writing, delivery, and pace, and I liked it about as much. The Sixty-Eight Rooms is an interesting book about a real-life art exhibit, the Thorne Rooms, and the not-so-real magical key that two children stumble across that cause them to shrink down and able to explore the rooms—and the worlds that lie beyond them. It’s part fantasy, part time-travel, and it’s fairly charming, though a little too simplistic for me.

The Sixty-Eight Rooms is an interesting book about a real-life art exhibit, the Thorne Rooms, and the not-so-real magical key that two children stumble across that cause them to shrink down and able to explore the rooms—and the worlds that lie beyond them. It’s part fantasy, part time-travel, and it’s fairly charming, though a little too simplistic for me. The Secret of the Skeleton Key is the first book in a code-breaking-themed series aimed for young readers, full of codes to crack (and a helpful reference guide and key in the back). The reader is invited to solve the mystery along with the characters and to decode the various messages (and chapter titles) along the way. It’s a fun, interactive book that code-loving readers would probably really enjoy, with a mystery simple enough and villains comical enough to draw them in.

The Secret of the Skeleton Key is the first book in a code-breaking-themed series aimed for young readers, full of codes to crack (and a helpful reference guide and key in the back). The reader is invited to solve the mystery along with the characters and to decode the various messages (and chapter titles) along the way. It’s a fun, interactive book that code-loving readers would probably really enjoy, with a mystery simple enough and villains comical enough to draw them in. Kazunomiya: Prisoner of Heaven takes place during the tense shogunate, Chained-In-Country/sakoku period, when the shoguns and the Emperor were at odds about opening up Japan to trade with other countries. The subtitle “Prisoner of Heaven” details Princess Kazunomiya’s feelings as being part of “Heaven” (a. k. a. the Imperial court), but completely powerless as she has little say in what goes on.

Kazunomiya: Prisoner of Heaven takes place during the tense shogunate, Chained-In-Country/sakoku period, when the shoguns and the Emperor were at odds about opening up Japan to trade with other countries. The subtitle “Prisoner of Heaven” details Princess Kazunomiya’s feelings as being part of “Heaven” (a. k. a. the Imperial court), but completely powerless as she has little say in what goes on. Lady of Palenque: Flower of Bacal is the most boring book in the Royal Diaries series yet, which is unfortunate because it’s probably the time/place in history that’s one of the least well-known. In fact, Kirwan basically admits in the notes at the end just how much she had to make up, including constructing an entire lineage for the main character (whose real name is unknown, but here has the name of ShanaK’in Yaxchel Pacal, otherwise to history known only by title).

Lady of Palenque: Flower of Bacal is the most boring book in the Royal Diaries series yet, which is unfortunate because it’s probably the time/place in history that’s one of the least well-known. In fact, Kirwan basically admits in the notes at the end just how much she had to make up, including constructing an entire lineage for the main character (whose real name is unknown, but here has the name of ShanaK’in Yaxchel Pacal, otherwise to history known only by title). Every so often, as I’m browsing books on Goodreads, I see Eva Ibbotson and I think “Oh, yeah! I like her!” This is only my third book by her, but I really enjoyed Which Witch? so I thought I would give her another shot.

Every so often, as I’m browsing books on Goodreads, I see Eva Ibbotson and I think “Oh, yeah! I like her!” This is only my third book by her, but I really enjoyed Which Witch? so I thought I would give her another shot. Sŏndŏk, Princess of the Moon and Stars is another typical book in the series, but I found this one a little bit more interesting than normal just because it presented a setting than I’ve read nothing about: ancient Korea. And while the book suffers from that “But did this actually happen?” syndrome as all the early Royal Diaries books do, I thought that this was a plausible and interesting story about what Sŏndŏk’s early life might have been like, and what might have caused her to build the Ch’omsŏngdae Observatory (the oldest remaining astronomical tower).

Sŏndŏk, Princess of the Moon and Stars is another typical book in the series, but I found this one a little bit more interesting than normal just because it presented a setting than I’ve read nothing about: ancient Korea. And while the book suffers from that “But did this actually happen?” syndrome as all the early Royal Diaries books do, I thought that this was a plausible and interesting story about what Sŏndŏk’s early life might have been like, and what might have caused her to build the Ch’omsŏngdae Observatory (the oldest remaining astronomical tower).